We’ve all seen the benchmarks. The new “Reasoning” models (like the o1 series or fine-tuned Llama-3 variants) claim to possess human-like logic. But after building my dual-RTX 4080 lab and running these models on bare-metal Ubuntu, I’ve started to see the cracks in the mirror.

Is it true “System 2” thinking, or just an incredibly sophisticated “System 1” pattern matcher? As an Implementation-First researcher, I don’t care about marketing slides. I care about what happens when the prompts get weird.

Here is my deep dive into the strengths and limitations of Large Reasoning Models (LRMs) and how you can reproduce these tests yourself.

The Architecture of a “Thought” in Reasoning models

Modern reasoning models don’t just spit out tokens; they use Chain-of-Thought (CoT) as a structural backbone. Locally, you can observe this by monitoring the VRAM and token-per-second (TPS) rate. A “thinking” model often pauses, generating hidden tokens before delivering the answer.

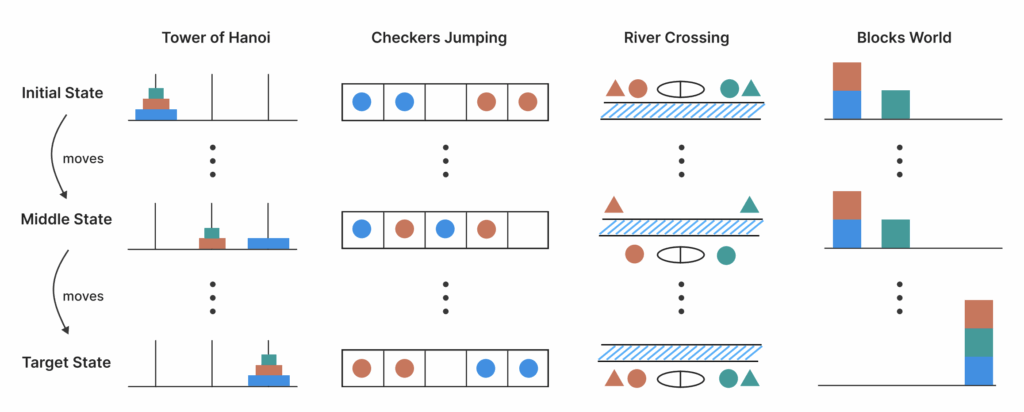

To understand the “illusion,” we need to look at the Search Space. A true reasoning system should explore multiple paths. Most current LRMs are actually just doing a “greedy” search through a very well-trained probability tree.

The “TechnoDIY” Stress Test: Code Implementation

I wrote a small Python utility to test Logical Consistency. The idea is simple: ask the model a logic puzzle, then ask it the same puzzle with one irrelevant variable changed. If it’s “thinking,” the answer stays the same. If it’s “guessing,” it falls apart.

Python

import torch

from transformers import AutoModelForCausalLM, AutoTokenizer

def test_reasoning_consistency(model_id, puzzle_v1, puzzle_v2):

"""

Tests if the model actually 'reasons' or just maps prompts to patterns.

"""

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_id)

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained(

model_id,

device_map="auto",

torch_dtype=torch.bfloat16 # Optimized for RTX 4080

)

results = []

for prompt in [puzzle_v1, puzzle_v2]:

inputs = tokenizer(prompt, return_tensors="pt").to("cuda")

# We enable 'output_scores' to see the model's confidence

outputs = model.generate(

**inputs,

max_new_tokens=512,

do_sample=False, # We want deterministic logic

return_dict_in_generate=True,

output_scores=True

)

decoded = tokenizer.decode(outputs.sequences[0], skip_special_tokens=True)

results.append(decoded)

return results

# Puzzle Example: The 'Sally's Brothers' test with a distracter.

# V1: "Sally has 3 brothers. Each brother has 2 sisters. How many sisters does Sally have?"

# V2: "Sally has 3 brothers. Each brother has 2 sisters. One brother likes apples. How many sisters does Sally have?"

Strengths vs. Limitations: The Reality Check

After running several local 70B models, I’ve categorized their “intelligence” into this table. This is what you should expect when running these on your own hardware:

| Feature | The Strength (What it CAN do) | The Illusion (The Limitation) |

| Code Generation | Excellent at standard boilerplate. | Fails on novel, non-standard logic. |

| Math | Solves complex calculus via CoT. | Trips over simple arithmetic if “masked.” |

| Persistence | Will keep “thinking” for 1000+ tokens. | Often enters a “circular reasoning” loop. |

| Knowledge | Massive internal Wikipedia. | Cannot distinguish between fact and “likely” fiction. |

| DIY Tuning | Easy to improve with LoRA adapters. | Difficult to fix fundamental logic flaws. |

Export to Sheets

The Hardware Bottleneck: Inference Latency

Reasoning models are compute-heavy. When you enable long-form Chain-of-Thought on a local rig:

- Context Exhaustion: The CoT tokens eat into your VRAM. My 32GB dual-4080 setup can handle a 16k context window comfortably, but beyond that, the TPS (tokens per second) drops from 45 to 8.

- Power Draw: Reasoning isn’t just “slow” for the user; it’s a marathon for the GPU. My PSU was pulling a steady 500W just for inference.

TechnoDIY Takeaways: How to Use These Models

If you’re going to build systems based on LRMs, follow these rules I learned the hard way on Ubuntu:

- Temperature Matters: Set

temperature=0for reasoning tasks. You don’t want “creativity” when you’re solving a logic gate problem. - Verification Loops: Don’t just trust the first “thought.” Use a second, smaller model (like Phi-3) to “audit” the reasoning steps of the larger model.

- Prompt Engineering is Dead, Long Live “Architecture Engineering”: Stop trying to find the “perfect word.” Start building a system where the model can use a Python Sandbox to verify its own logic.

Final Thoughts

The “Illusion of Thinking” isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Even a perfect illusion can be incredibly useful if you know its boundaries. My local rig has shown me that while these models don’t “think” like us, they can simulate a high-level logic that—when verified by a human researcher—accelerates development by 10x.

We are not building gods; we are building very, very fast calculators that sometimes get confused by apples. And that is a frontier worth exploring.

See also:

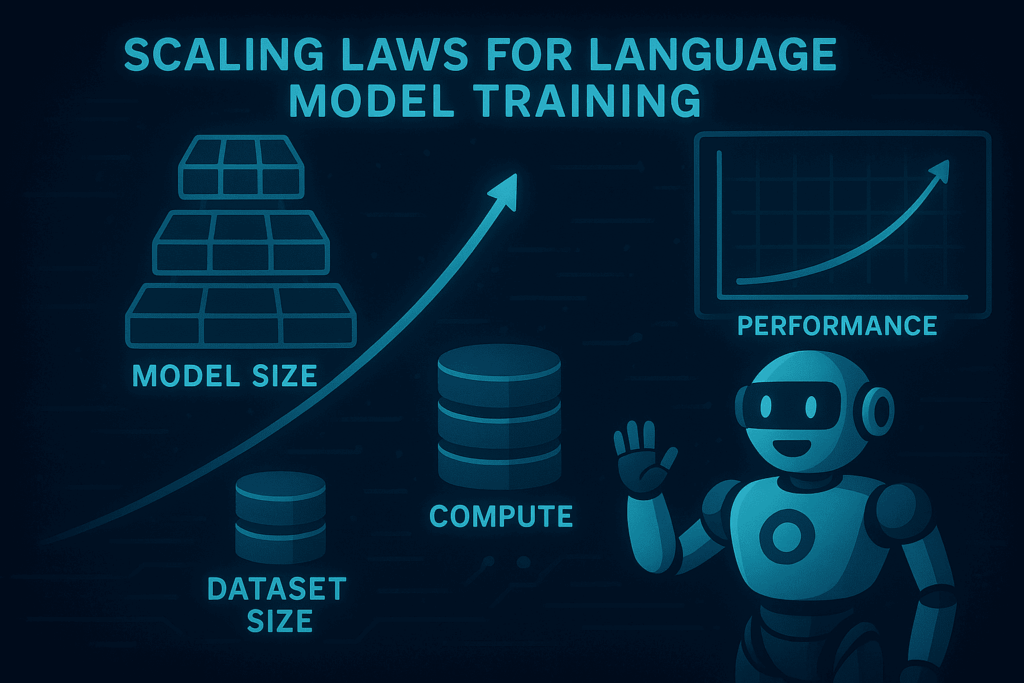

The foundation for our modern understanding of AI efficiency was laid by the seminal 2020 paper from OpenAI, Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. Lead author Jared Kaplan and his team were the first to demonstrate that the performance of Large Language Models follows a predictable power-law relationship with respect to compute, data size, and parameter count.

Once a model is trained according to these scaling principles, the next frontier is alignment. My deep dive into[Multi-Agent Consensus Alignment (MACA) shows how we can further improve model consistency beyond just adding more compute.